Jim Davis

Accident Report – precis and analysis

A/C: Piper PA-46-350P, N5EQ

Place: Goose Bay Airport, Newfoundland

Date: 14 December 2022

This report is to advance safety – not to assign fault or liability

History of the flight

At 0820, the privately registered Piper PA-46-350P (with the JetPROP DLX conversion) departed SeptÎles Airport, Quebec, on an IFR flight to Goose Bay with the pilot and a passenger on board. They were returning the aircraft to its home in Europe, following avionics upgrades in the U.S.

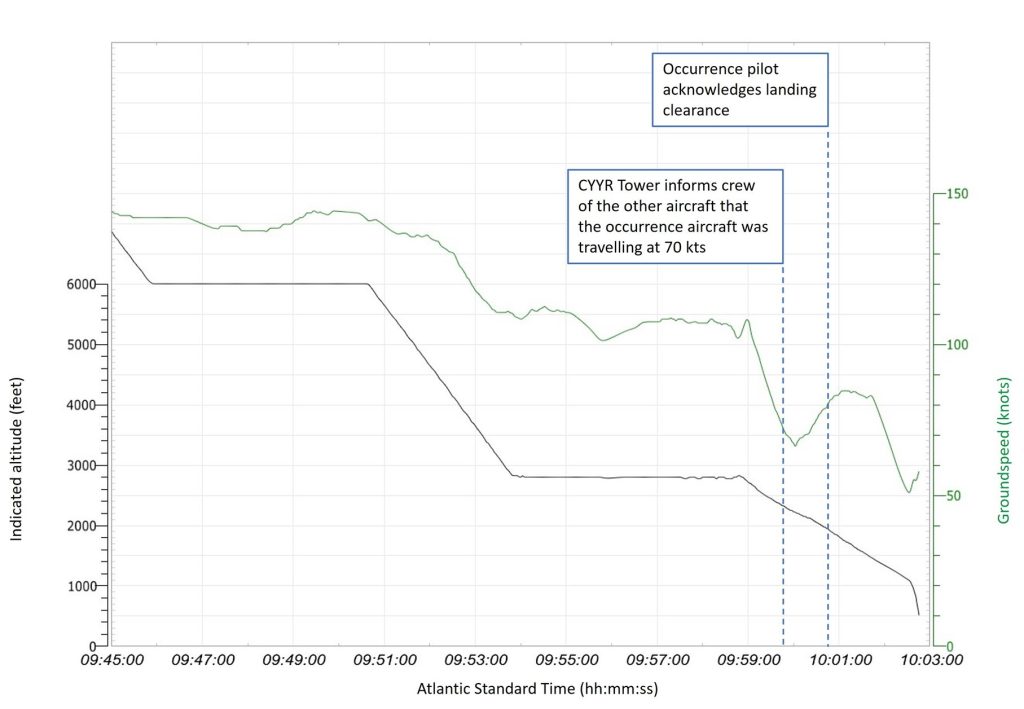

According to the ADS-B, at 0928, when the aircraft was about 85 NM from Goose Bay, it began a descent from flight level 230 and was cleared for the RNAV approach to runway 08.

At 0958, the aircraft crossed the final approach fix FAFKO at 2800 feet ASL, at a ground speed of 104 knots, and began the final descent.

Although the descent remained steady on a 3° profile, the ground speed decreased continuously for about 60 seconds.

At 0959:50, it was on a 7 mile final at 70 knots. The groundspeed then decreased to 67 knots before increasing again however it remained on a steady 3° approach profile.

At 1000:31, the pilot reported at waypoint SATAK, and the ground speed increased to over 80 knots. The tower reported the wind as 050° magnetic at 16 gusting to 22 knots. and cleared the aircraft to land on Runway 08. The pilot acknowledged at 1000:49.

Two minutes later the ground speed decreased to 51 knots. The aircraft departed controlled flight and impacted terrain when it was about 2.5 NM southwest of the airport.

The ELT activated, and a helicopter arrived three minutes later and took the occupants to hospital. The pilot died of his injuries and the aircraft was destroyed.

Pilot information

The pilot had 2260 hours, 594 of which were IF and 1046 hours were in single-engine turbine aircraft.

He held an FAA CPL and Instructor rating and a valid medical certificate.

There was no indication that his performance was degraded by fatigue.

Weather

The CYYR 1000 met report indicated:

- wind 030° at 16 – 22 knots;

- visibility 15 SM;

- overcast ceiling at 1000 feet AGL;

- Temp 1 °C and dew point of −1 °C;

- Altimeter 30.52

Aircraft information

The aircraft was a Piper PA-46-350P modified with a Pratt & Whitney Canada PT6A‑35 turboprop engine . The aircraft is known as a JetPROP DLX. It is certified for single-pilot operation in IFR and in known icing conditions. It has a stall speed of 69 knots clean and a 58 knots in the landing configuration.

The STC brought the fuel capacity from 120 to 151 USG.

The aircraft had flown 12.3 hours since the last MPI and the avionics upgrades, which included installing a Garmin GFC 600 autopilot system, dual electronic flight instruments, and a Garmin GI 275. An Alpha System AoA angle of attack indicator and upgrading the primary flight display Aspen Avionics EFD1000 to enable synthetic vision.

Both EFI units could retain air data, attitude, and heading reference system logs.

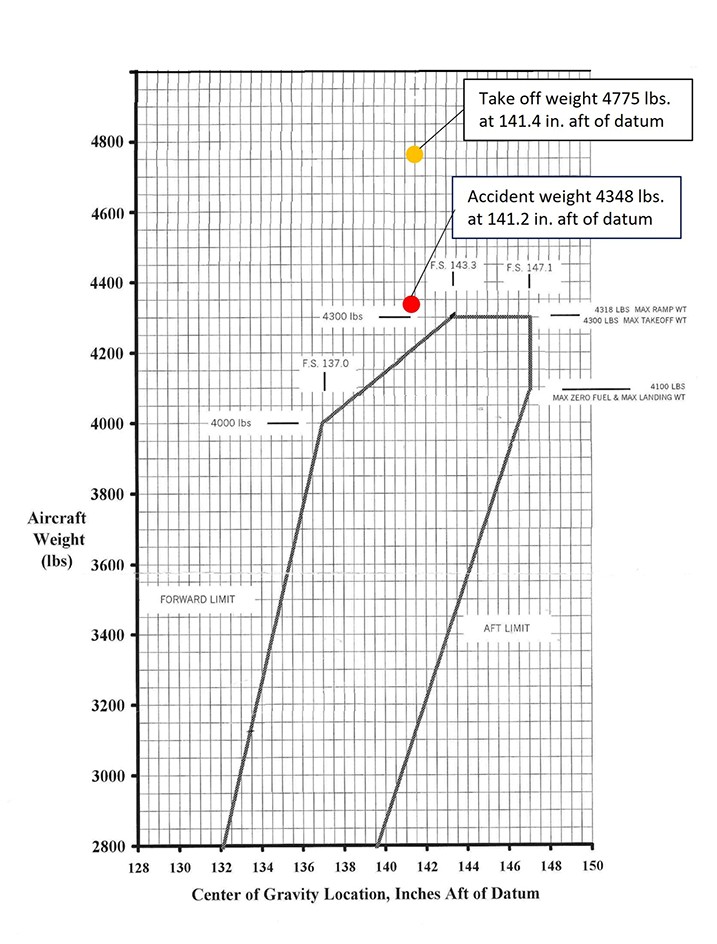

Aircraft weight and balance

The maximum take-off weight was 4300 pounds, with CoG limits from 143.3 to 147.1 inches aft of datum.

The aircraft departed with full fuel. The weight and balance report listed the useful load as 1217 pounds. With full fuel, there would have been 160 pounds available for occupants and baggage.

The actual takeoff weight was 4775 pounds and the CoG was 141.4 inches aft of datum. At the time of the accident the weight was 4348 pounds and the CoG was 141.2 inches aft of datum.

It could not be determined whether these figures contributed to loss of control.

An overloaded aircraft will have degraded performance. Increased takeoff and landing runs, increased stall speed, decreased rate of climb, decreased cruise speed, and reduced range.

The weight distribution is critical – it affects both stability and performance. A forward CoG increases the stall speed.

To keep the mass and balance within limits pilots must plan for reduced fuel loads when carrying pax and baggage.

The AFM says: Although the airplane offers flexibility of loading, it cannot be flown with the maximum number of adult passengers, full fuel tanks and maximum baggage. With flexibility comes responsibility. The pilot must insure that the airplane is loaded within the envelope.

Approach speed

According to AOPA Pilot magazine the key to a stabilized approach is to slow the pace of the critical final segment. If you’re doing it right and stabilize early, it seems that there is nothing left to do. At this time on the approach you are primarily monitoring, not manipulating, and that is better for situational awareness.

The accepted method of controlling an aircraft’s descent profile to achieve a stable approach is by using the elevator to control pitch, which in turn controls airspeed, and engine power to control the rate of descent.

However, the Garmin GFC 600 controls airspeed with power

The investigation found that the autopilot was engaged for the approach; however, it could not confirm this for the last 60 seconds.

The AFM calls for a final approach speed of 90 KIAS with full flaps or 100 KIAS flapless.

Two companies that train in the JetPROP DLX suggested that the final approach be flown at a minimum of 120 KIAS for better pitch stability.

Impact and wreckage information

Strike damage on trees indicates a final descent angle of 37° at a wings-level attitude and a low-speed loss of control.

The landing gear was down and the flaps were between the 0° and 10°.

Significant power was being produced at impact. There was no sign that a component or system failure contributed to the accident.

There were no signs of ice accumulation.

EFI data for the last 60 seconds could not be recovered so the investigation could not determine what led to the loss of control.

Jim’s Comments

I don’t know exactly what happened, but that doesn’t matter – this accident points to stuff that could be dangerous to us. So I went through the report with a yellow highlighter and here’s what jumped out at me:

Avionics upgrades. These are extremely smart boxes with many buttons that can kill you if you don’t understand them. There were four of them newly installed in this aircraft. So there was much to puzzle the pilot.

Imagine they had installed a dirty great brass lever with a red handle labelled DANGER. You and I would be extremely hesitant to move it, but we are happy to push buttons that we don’t fully understand.

The pilot was obviously a clever guy – he had well over 2000 hours, including 600 of IF and over 1000 hours on single-engine turbines.

However, there is no requirement that he understands a single feature on any of these new boxes. Are they interconnected? Do they supply redundancy? Which external sensors or aerials feeds which box?

And those are the easy questions. Here’s one that possibly killed him. Did he know that the Garmin GFC 600 calls for airspeed control with throttle, and rate of descent with attitude. This is opposite to the normal way of flying a light aircraft. Did the Garmin GI 275 command the autopilot to do things in this unusual way? Did it take the pilot unawares.

The graph shows a steady 3° approach profile while the airspeed (actually the groundspeed) varied enormously. This suggests the pilot was battling to keep speed and glideslope under control. This should have been easy for a pilot of his experience unless he was fighting Mr Garmin’s thinking.

It takes any pilot a while to learn new equipment, and a lot longer to burn that knowledge into his soul so he would automatically do the right thing under pressure.

The Gleitch tells me he read that it takes at least ten hours of dual to settle down with a new black box. So would four boxes call for a 40 hour ‘conversion’? Legally no conversion is mandated – you can blast off into the muck with no dual at all.

Would I be happy to sit in the back of an aeroplane in IF conditions with a pilot who wasn’t familiar with all these clocks?

NOPE.

Fatigue. The report says the pilot’s performance was not degraded by fatigue at the end of a nine hour flight. Mine would be.

Weight. At takeoff the aircraft was close to 500 pounds over-gross.

Balance. At takeoff the CoG was 1.9” ahead of the forward limit. When it crashed this had increased to 2.1”.

Approach speed. The POH calls for 90 KIAS with full flap. This makes sense as it’s just over 1.3 times the 58 KIAS in the landing configuration.

It seems incredible that two schools which convert pilots to these aircraft both call for a minimum approach speed of 120 kts. That’s 30 kts faster than the POH figure.

Take home stuff

- Heed the POH warning about balancing fuel capacity against payload: With flexibility comes responsibility.

- Beware having your aircraft better equipped than you are; just as fitting lights to your aircraft does not make you night rated.