Laura McDermid

Craig Ritson is one of those rare people you meet once and never forget. Born in Eshowe and raised in Pinetown, he has spent more than 25 years in the United States, yet still speaks with an unmistakable South African accent.

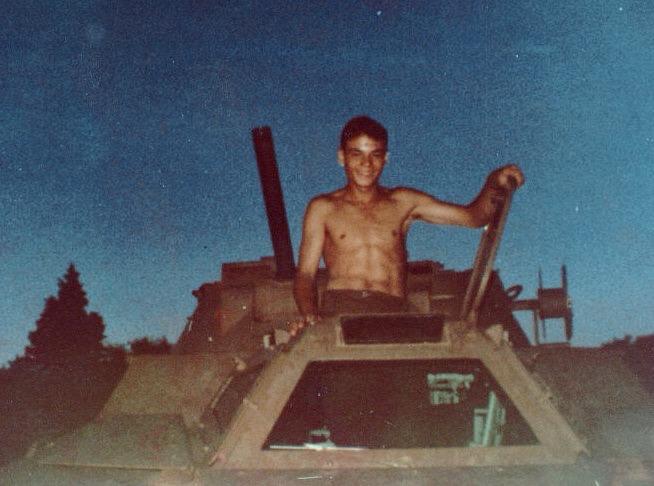

The most striking thing about Craig, however, is that he has only one hand. In 1984, at just 18 years old, he lost his left arm below the elbow when a mortar shell exploded in the Ratel he was driving during a national service training exercise in Bloemfontein.

He spent three weeks in an induced coma, and when he awoke, his first question to his mother was, “Where’s my watch?” That was the moment the reality of his injury sank in. The blast also left his body embedded with shrapnel — something that creates endless amusement at airport security. “I set off every scanner I walk through,” he laughs.

Craig has never allowed his injury to define him. He is relentlessly positive, refuses to see himself as a victim, and has lived a life of adventure many able-bodied people would envy.

Aviation was part of his upbringing. His father was a pilot, and Craig grew up assuming that garages were for aircraft projects rather than cars. His father owned a Breezy and an Aeronca Champ, and by 14, Craig was already flying the Champ under his father’s watchful eye.

While other teenagers spent holidays at the beach, Craig preferred the airfield, assisting with projects and helping with maintaining aircraft.

That same year, tragedy struck. His father was killed after flying the Breezy into a power line shortly after take-off from Allemanskraal, returning from an EAA convention. A week later, a family friend took him flying in a Cub, but his mother — understandably — was wary of his continued interest in aviation.

It would be another decade before Craig flew in a light sport aircraft again. While living in Mmabatho, a friend invited him up in a Forney F1-A Aircoupe, and the spark was reignited.

In 1995, Craig and his wife travelled to the United States on holiday, fell in love with the country, and decided to stay. A colleague with his own plane introduced Craig to a local aviation museum, where he helped with the restoration of Beechcraft Staggerwings whilst enjoying many flying opportunities.

By 2002, his wife was encouraging him to earn his PPL. At first, he wore a prosthetic arm, assuming he would need one to pass his medical. His daughter, Lisa, jokingly dubbed it the “pathetic arm” — more hindrance than help. After it jammed in the yoke of a C152, Craig abandoned it entirely. The FAA had already put him through every manoeuvre and declared him fit to fly without it.

His instructor sent him solo after just three lessons, though it still took 90 days to log the 50 hours required by law.

That first solo remains vivid in his memory: the sudden awareness that he was entirely on his own, and the pure exhilaration of completing the flight and landing smoothly. “It’s a feeling you never forget,” he says.

With a young family, renting aircraft wasn’t an option, so Craig bought a partially built Sonex with an 80hp Jabiru engine, which he nicknamed ‘Gupta’. It was 60% complete, and within two years, it was in the air. He still owns it today — his wife calls it his “aluminum mistress.”

His friend Matt, who was building an RV-7A, would always ask after the Sonex, and Craig’s standard reply was, “My RV wannabe is doing great.” When Matt completed his PPL, he realised flying wasn’t for him. The two met annually at Oshkosh, and in 2016, when Matt again asked about the Sonex, Craig gave the same answer.

In a remarkable act of generosity, Matt offered him his half-built RV-7A. They agreed on an affordable payment plan, and the following weekend, Craig drove to Columbus, Ohio, to see his new project. Matt and his brother delivered it the next week. It took Craig another five years to complete the build, but in 2023, he finally flew the -7.

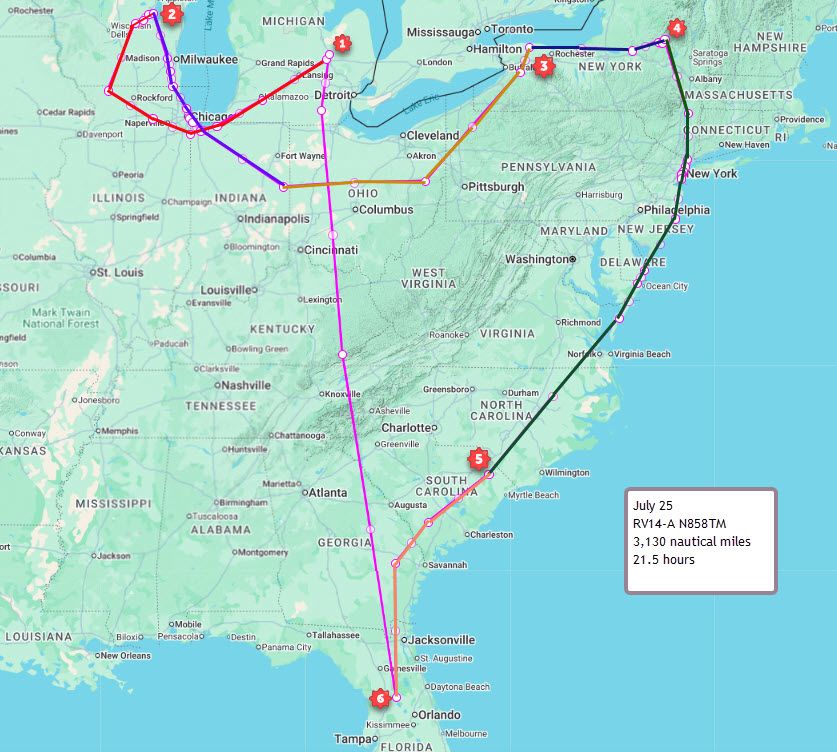

His first cross-country flight was the 1000 nm from upstate New York to Sun ’n Fun Florida, with Matt in the right seat. They rolled, looped, and laughed their way through the trip — and Matt had no regrets. Instead, he turned his energy to running marathons, ultimately setting the world record for the fastest average marathon time on every continent.

After years in upstate New York, where winter grounded him for half the year, Craig relocated to an aviation estate in Weirsdale, Florida — an hour north of Orlando — where he can fly year-round. It’s also home to EAA Chapter 1236, where Craig is deeply involved in restoration projects. The move was strategic: inland to avoid hurricane-driven insurance hikes, and right on a runway for maximum flying time.

Next on his list? An instrument rating — not for career reasons, but because he would like to do his instructor’s rating so that he can share his passion with the next generation of aviators.

Craig has shown that adversity does not have to define us for the worse. He is living proof that while we cannot always choose our circumstances, we can choose how we respond to them. His passion for life and his love of aviation are infectious and any student lucky enough to have him as an instructor will be privileged.