NAV MADE EASY

M is a friend for whom I am acting as a sort of long-range mentor as she finds her way into instructing. One of her pupes has a mental block about navigation. He says it’s too complicated – he’ll never understand it so he’s going to give up flying.

Well, dear M, I suggest you start at the beginning. Tell your pupe the true story of how navigation first began.

It happened when Fred Flintstone wanted his son, Ferdinand, to retrieve a chunk of brontosaurus meat from the creature he had slayed on Thursday.

“Go towards that volcano for half a day and you will find the remains of the stupid animal. Bring back its liver – your mother wants to make some pate for the Brownstones when they come round for cocktails tomorrow evening.”

He raised a bushy eyebrow to see whether the acned youth had uploaded this directive. When he judged that his son had embraced the plan he issued his final instruction. “Bugger off now and you will get there by sunset.”

That is the foundation of all nav. Young Ferdinand had a heading to steer, and an ETA.

And that’s exactly what nav is about to this very day – you are looking for:

- A heading to steer, and

- An elapsed time – which will give you an ETA.

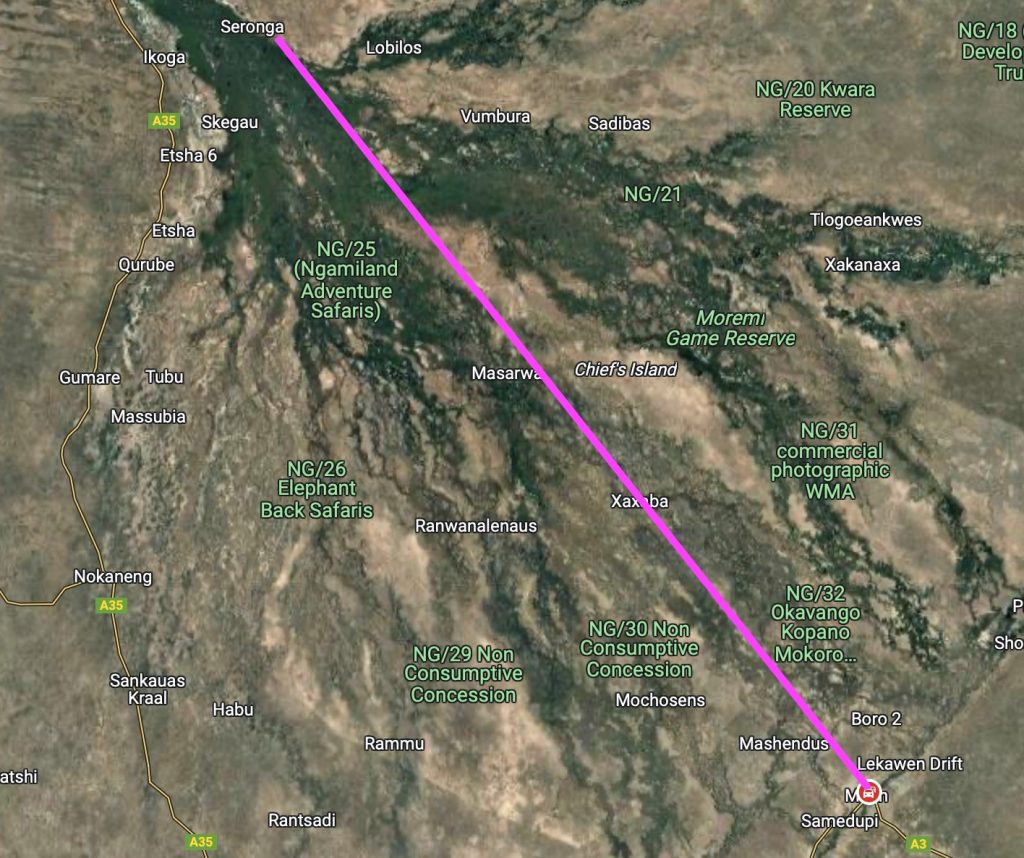

Okay let’s see how this still works two million years after the Flintstones laid the foundations. You want to fly from Maun to Seronga in the middle of the Okavango Delta in Botswana. Uncle Donald has turned off the world’s GPS because of his squabble with Comrade Vladimir.

What heading are you going to steer and what time will you get to Seronga if your C172 cruises at a block speed of 100 mph and you kick off at 08.00?

Those who are familiar with the Okavango Delta will tell you there are no trustworthy landmarks. The scenery is flat and the islands appear, grow, shrink and disappear with a will of their own. And there are no roads, rivers or railway lines to offer guidance.

You need two more bits of info – the distance, and the variation. Google says it’s 101 miles, so that’s one hour’s flying – we don’t work in half minutes. And the variation is 11°W.

I have just stuck a protractor on the chart and measured the angle round from True North – it’s 322°.

It’s really that easy. Steer 322° plus the 11°, so that makes your ‘magnetic’ heading 331. Hold it for one hour and you will fly slap over Seronga.

Okay, we have come to a bit that needs explaining. The ‘magnetic’ heading is simply the heading you will steer on your magnetic compass. But only if the instrument is dead accurate. Unfortunately it’s not always – it can be a few degrees out.

However that’s no problem, the compass has a little card next to it to tell you about its slight deviations from the truth. This is conveniently called a deviation card. More about this later.

Soon after takeoff, ATC wants to know your ETA for Xaxaba (pronounced Kikaba). You glance at the map and it looks like about a third of the distance, so it will take a third of an hour. That’s 20 minutes. So your ETA will be 08.20.

Those who have flown around the Delta in the days before the magenta line will confirm that’s exactly how it works.

So all this basic navigation stuff must be in your head in case your Garmin whiz-bang falls on its face.

How are we doing so far M – anything there too complicated for your pupe?

I hear grunts and murmurs of disapproval from those members of the congregation who are still awake. “The bastard’s cheating. He hasn’t mentioned the bloody wind.”

Well spotted indeed, O faithful sheep. So let’s talk about the wind.

Again we’ll start with the basics. So young Ferdie Flintstone wouldn’t have had trouble with wind. Well, he might have done – we know little of his medical history – but it shouldn’t affect his nav. His heading towards the volcano, and his speed over the ground were steady, regardless of wind. And that brings us to the crux of the matter. Us clever piloting people see wind differently.

To us wind is a block of air that moves over the ground.

Now please repeat that seven times until it is branded into your temporal lobe like one of those nasty sizzly things they do to cattle. It’s crucial to both navigation and to aerodynamics, so here are a few ways to get your pupe to think about wind.

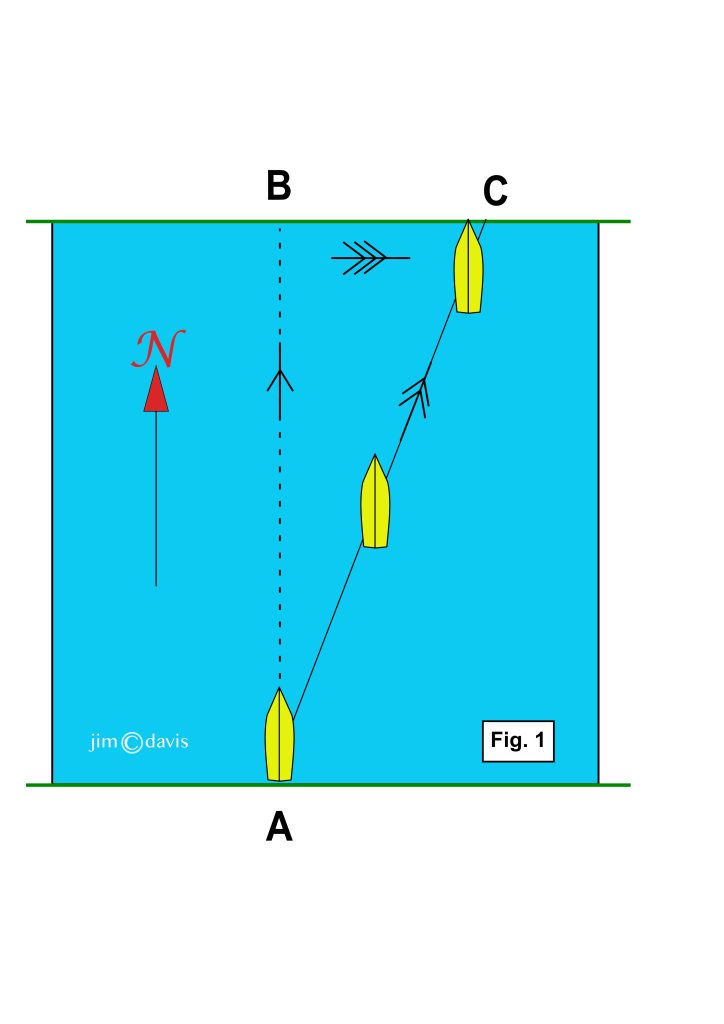

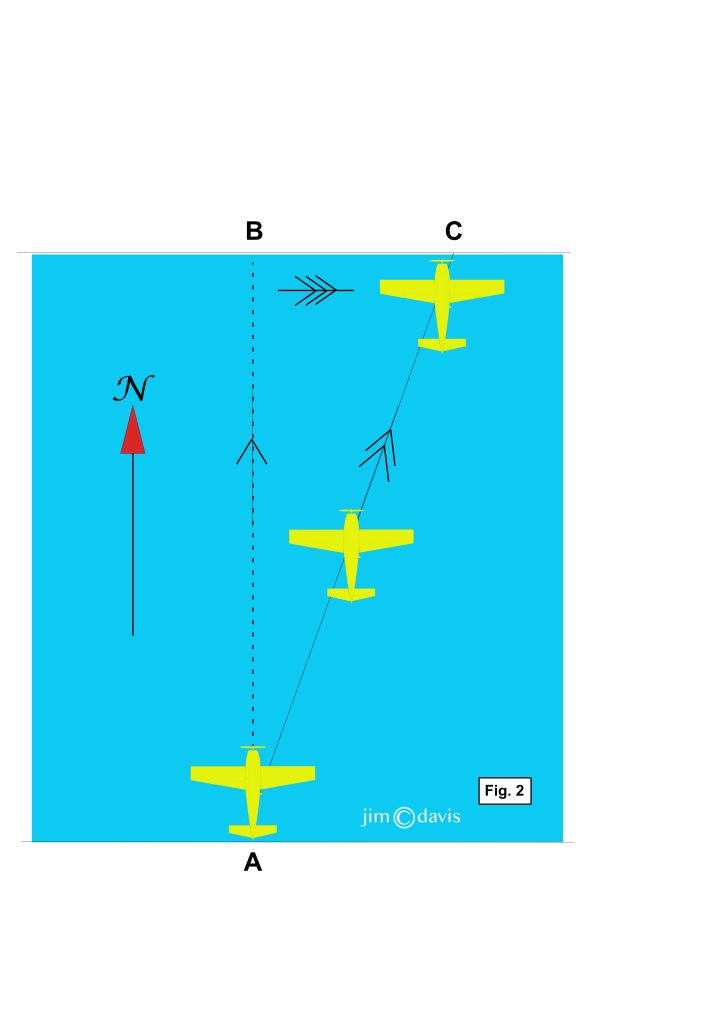

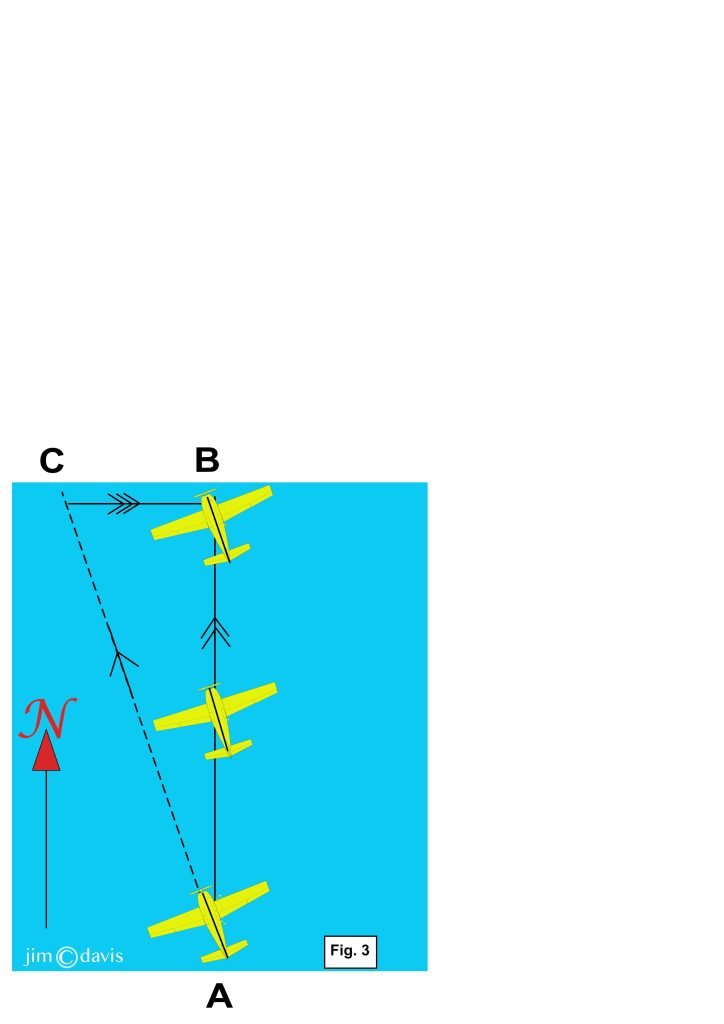

Get them to have a very good look at Fig.1. It looks simple enough but there’s more to it than meets the eye – not difficult stuff, but it explains the number one basic problem with navigation.

Bloody wind.

If there was no wind, then you wouldn’t need to navigate – you would simply point the plane in the right direction and arrive at your dest on time.

Cast your mind back to when you were an adorable child called Andy – that’s you at A for Andy. You have a battery powered toy boat that you want to send across a river to your adorable sister – B for Barbie – on the other side.

You point it at her and let go. You are appalled to see the current take it downstream. It’s going to wind up at C for Charlie Brown who may abscond with it. This happens despite the fact it’s still pointing the right way.

Now take a look at the little arrows on the lines

The single arrow – indicates the way you are pointing – this is called your heading. In this case your heading is due north.

Obviously your boat is not going where it’s heading. It’s being carried to the right because it’s environment – the river – is moving that way.

It’s the same as when you step on to a bus. That vehicle suddenly becomes your environment and you will go wherever it goes.

It’s easy to think the boat goes sideways because the river pushes on the side of it. But that’s not the case. The boat has become part of a moving environment. In the same way that the bus doesn’t keep pushing you as it travels – you have simply boarded a moving environment.

You may have been subjected to the irresistible will of a sergeant with the three arrows on his sleeve. You don’t argue, you simply go where he tells you. That’s what happens when the water carries you along, so it’s also labelled with three stripes.

Finally the track that the boat actually follows is marked with two arrows – like the tracks of your car when you drive through the bush.

So in summary you have:

à to indicate your heading – the way you are pointing.

àà to indicate your track – your path over the ground.

ààà to indicate the movement of the water.

There is one more element to this – speed. Let’s say your boat has a super turbo-boost afterburner and it travels at 20 mph and the river is flowing at 1 mph. Then Charlie Brown won’t get his hands on it because it will only move a little way downstream of Barbie.

But if it’s the other way around and the river is roaring down at 15 knots and your miserable little boat only chugs along at two knots, then it’s going to be out of sight by the time you wake up.

So the relative speeds of the boat and the river will determine your track and your groundspeed.

This means that those lines with little arrows tell us more than we thought. They are in fact vectors which, by definition, always consist of two things – a direction and a speed. The longer the line the faster the speed

So a vector is a speed and a direction.

Now we have a full picture of the dreaded vector triangle. No more surprises, I promise you.

This is what it is in aviation language:

à is your heading and your airspeed

àà is your track and your groundspeed

ààà is the wind direction and speed

Obviously the river is the same as wind – it’s a chunk of water that’s moving over the ground in exactly the same way that wind is a block of air that’s moving over the ground

Yep, I’m labouring the point, but it’s vital info that you carry this knowledge with you for the rest of your life.

How much will the river effect your boat? The answer is 100%. The boat will move downstream at exactly the same speed as the river. And an aircraft will move at exactly the same speed as the wind. And when you board a bus you move at exactly the same speed as the bus. And if you carry your gold-fish bowl across the room the hapless ichthyoid moves perfectly with her environment.

Please make sure your pupe understands at least one of these examples. Not only are they critical for navigation, they are also life-saving when confronting the dragons of the downwind turn. But that’s for another day.

So let’s focus on the boat one last time.

If you know that the river is moving at say ten metres per minute and it takes five minutes to cross the river, then it will move 10 x 5 = 50 meters downstream by the time Charlie Brown gets his hands on it.

Now here’s the crux of the thing. It doesn’t matter a damn which way the boat is facing during its crossing – it can zig-zag or do couple of 360s – as long as it is supported by the water it will travel at exactly the water’s speed.

In the same way that, as long as you are in the bus, you will travel at exactly the bus’s speed. And an aircraft, as long as it is supported by the air will travel at exactly the speed of the wind.

So that’s not difficult is it? But it’s the bit everyone thinks is difficult.

When the met man says there is a 20 knot wind from the north (360/20). This means that in one hour it will carry you 20 nautical miles south of where you would be in no wind.

Get it?

Got it.

GOOD!

Oh, and a quick PS. If you see the word ‘course’ delete it, burn it, chuck it out. The word became mangled in mid-Atlantic. The Brits thought it meant heading and the Yanks thought it meant track. Now it mostly does means track, but don’t trust it.

Right, now we know what the wind will do to us, we can work out what heading we should steer to allow for it.

There are at least five ways to do this:

- You can push buttons on your GPS

- You can draw it out to scale

- You can work it out with trig

- You can use the one in sixty rule

- You can use your E6B whiz-wheel

To get a PPL you only need to do the last. But if you want to have the greatest possible fun and be professional, you will draw an A to B line on a paper map and then look outside and watch how the countryside conveniently conforms to your plan.

If you have a GPS put it on the back seat and switch it on occasionally to make sure it’s not broken.

Okay so this is how to use the E6B.

Remember that with the vector triangle we have six variables. If you know any four of them, then you can work out the other two. That’s a stroke of luck because when you are flying you usually have four of them.

- You know your required track – you want to go from A to B.

- You know your airspeed – that’s in the POH

- You know the wind direction from the met man

- You know the wind speed from the met man

- You want to know what heading to steer to allow for the wind

- You want to know what groundspeed to expect in that wind

You could draw it out to scale, but that’s tedious so Secret Agent E6B has devised this mechanical triangle of velocities to save you the trouble.

Let’s dive straight into an example: The instructions – which are often printed on the computer – say:

[GUYUS please insert the box called “For Hdg & G/S problems”]

So here’s a problem: You want to fly from A to B. You measure the track from true north – it is 270. Your aircraft cruises at 115 kts and the wind is given as 045/20.

What heading will you need to steer to compensate for the wind? And what will your groundspeed be?

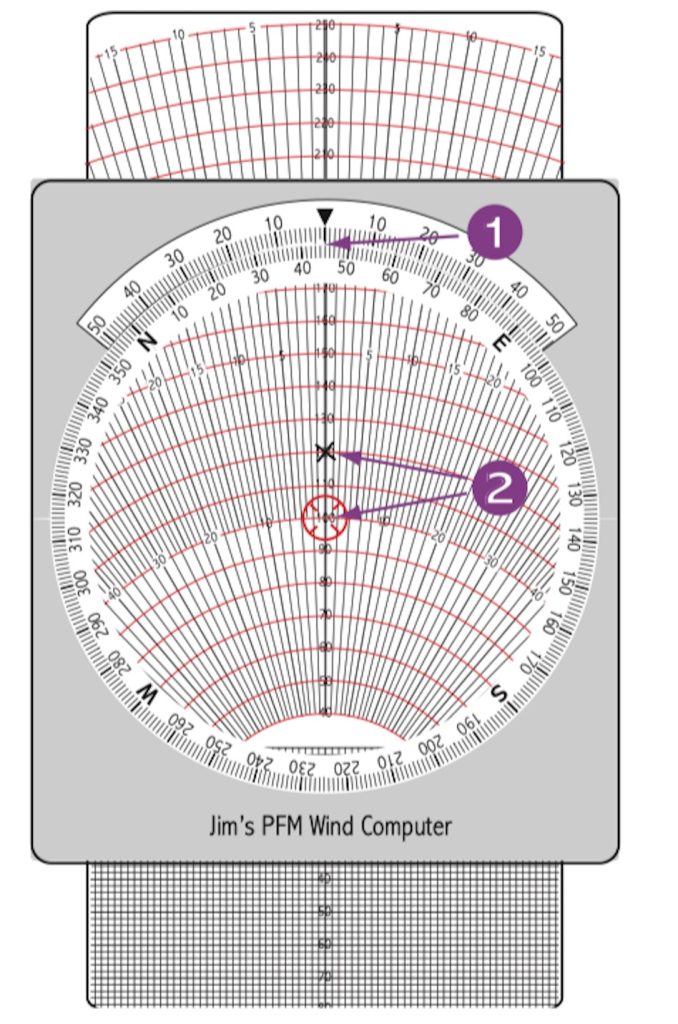

Easy just follow the instructions labelled 1 and 2 on this diagram.

Turn the scale until the wind direction of 045 it opposite the pointer at the top.

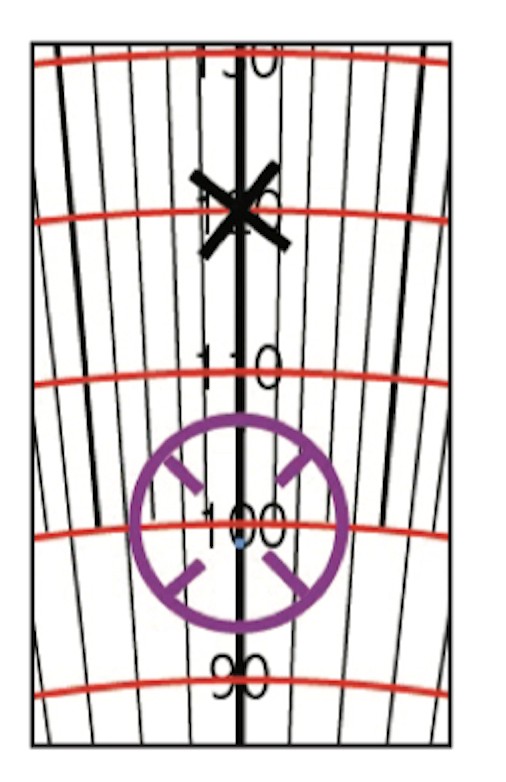

Slide the speed scale to get any whole number under the centre and then mark an X for the windspeed of 20kts UP from the centre.

So now you have entered the wind into your computer.

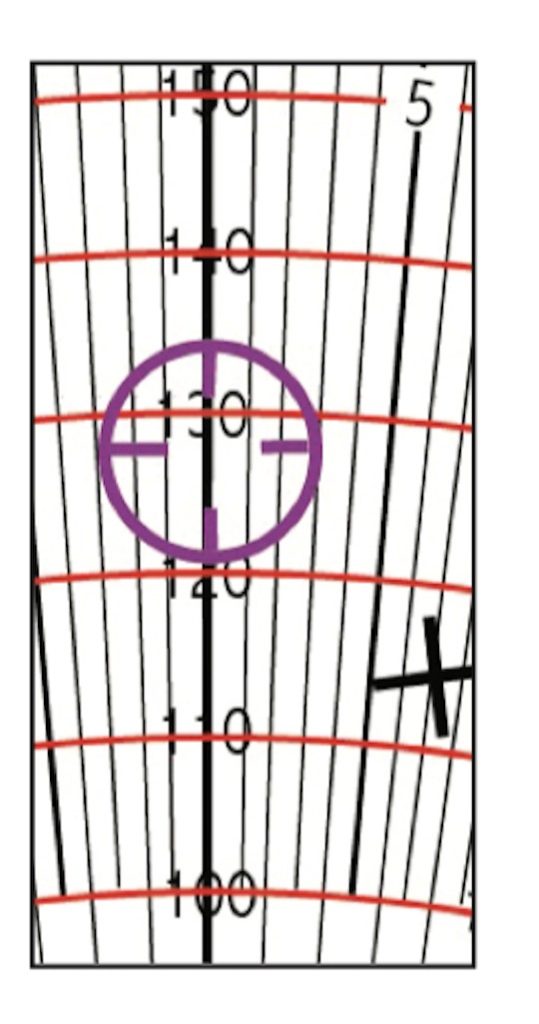

Next set your required track of 270° under the pointer.

Move the slide down (don’t turn anything) until the wind X is midway between the red 110 line and the 120 lines – to give 115kts.

Now read your groundspeed under the centre – 127kts. This means the wind is giving you a nice boost.

Finally, read the drift angle of 7° under the X, from the radiating black lines. Use common sense – you will need to steer into the wind to allow for drift, so you must add the 7° to your 270° to give a heading of 277°.

Couldn’t be easier.

Instructors, remember the vital phrase – involve me and I will understand. So get your pupe to practice a few of these. The first one is always a bit ponderous, but after a few. they will go quickly and easily.

So now you know what a vector triangle is, and how to build one by following the instructions written on your E6B.

Next time we get down to the fun bit of keeping the outside picture the same as the inside picture – called a map.