RSR #34

Last month we looked at the theory behind map, clock and compass (MCC) nav. It’s the basis of ALL nav. Now let’s put it into practise.

2500 years ago Confucius said, ‘Life is simple, but we insist on making it complicated.’ Then in 1960 Kelly Johnson – Lockheed’s chief engineer – condensed it to KISS – Keep It Simple Stupid (Keep it Simple Sonny or Keep it Short and Simple.) Then in 1985 I said it to Pupe Propwash.

Here’s what happened:

My phone rings. “Hello. This is the Cape Aero Club. One of our chaps, Pupe Propwash, is having a spot of bother with his cross-country. You see he set off steering 043 compass in order to maintain 046 magnetic, which gave him a true track of 058 allowing for the forecast upper winds of… hello hello… you still there? You see with a wind of 170/20, this would blah blah….”

Basically, Propwash had set off on a multi-leg solo nav – with about a hundred check points. His flight-log looked like Anglo American’s financials.

He became comprehensively lost behind the mountains, which cut off VHF contact. A military Dak was relaying messages between the adventurer and Cape Town Information who had suffered a sense of humour failure.

The whole thing was getting out of hand until Propwash spotted the coast, and everyone relaxed – incorrectly, as it turned out.

You see, because that part of our coast is roughly “L” shaped, and young Propwash didn’t know which coast he had found. If it was the North coast, a left turn would return him to base, while if he was on the south coast a right turn would take him home.

It wasn’t a good day for coin-tossing, hence the phone call. He had turned away from mama and was heading along the South coast towards my little flying school in George, nearly 200 miles away.

Of course you could ask, what about his compass? Surely that would tell him he was going the wrong way? It would indeed, but by now the poor guy didn’t know the difference between 003, 030 and 300, and wasn’t remotely interested. He just wanted somewhere soft to land.

I shot up to the tower and we nursed him in and gave him coffee while he showed me a young mountain of paper designed to add needle-sharp accuracy to his navigation. I conceded that I too was bewildered by the numbers.

Propwash had so much office-work there was no time to look out and see where he was going. He was searching for little things – like the place where a dirt road made a kink near a radio mast. The big picture, consisting of cities, coastlines and mountain ranges were of no interest to him. He was looking for his next microscopic check-point which should be 2¼ miles away.

Darling instructors, please don’t do this to your little treasures. Go for the big picture and little paperwork.

Here’s how it works. You need a well-prepared map, with fuel figures scribbled in the margin, and a frequency chart in your shirt pocket. If you keep the big picture in mind, that’s all you need for a VFR flight. Panic not – I will explain.

Imagine you takeoff and fly to a familiar point that you can see 12 miles away, and from there head to another landmark, and thence 15 miles along the railway line to the next place. Augment this with the big picture and a bit of common sense and you can’t go wrong. No GPS needed.

This chat is for student pilots, who are not allowed to rely on GPS. And it’s for ordinary people who enjoy navigating by looking out the window.

Naturally, if you want to cross oceans, deserts and rain-forests, and places that make your nought pucker, it makes sense to talk to the satellites.

But this is for instructors and weekend pilots. It’s the basics. It works well and it’s a whole lot of fun.

Map-only nav system

Let me explain how the map-only nav system works. You get the newest maps available. I like the 1:1 000 000 WAC (World Aeronautical Charts). But the 1:500 000 is useful around large built-up areas.

In this example you draw in a good solid black line, from Grahamstown to Queenstown with a Fineliner. You then measure off 20 nautical mile markers. Do NOT use time marks because they change with wind and aircraft type. 20 mile markers work for any aeroplane from a Cub to a King Air.

If your track leaves a map, just stick in an arrow where it joins the next and write “To Bethlehem”. And where it comes on to the next map put and arrow saying “To Grahamstown”. This makes it easy to know which line goes where next time you use the map.

Now, alongside your track, you draw in a nice bold box with a point at one end, and write in your magnetic track. That is the track you measure with your protractor, plus or minus the variation. Do this on an empty part of the map – so you don’t obscure something important.

I draw in the runways at my destination, alternates and possible pee-stops along the way.

When you have finished, your map should look something like this:

[Please stick the map here – “Map Grahamstown to Queenstown.png”]

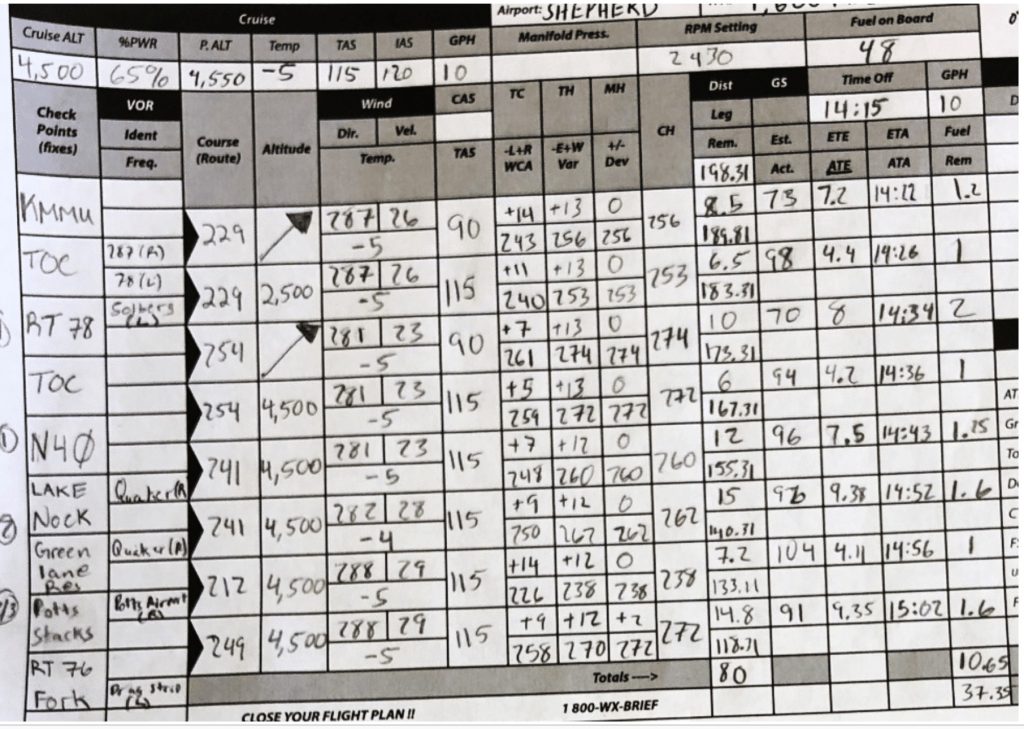

We have now got rid of Propwash’s wheel-barrow load of numbers crammed into tiny boxes. Below is the sort of thing I am bitching about. This horror is the pride of an FAA testing officer. I hope you never have to fly with him.

Don’t just skip past this disgusting document – have a good look at it and then make sure your pupes never go down this road.

Okay this is: “BRYAN Flight Log.jpg”

First, the word ‘course’ is a NO-NO – we discussed it before – the Brits think it means heading, and the Yanks use it to mean track. Then there is ‘TC’ for True Course. Who cares about True North? We are not going to use it in the cockpit so don’t have it there.

Next, the “+/- Dev” column is BS – he’s put zeros all the way down – really?

But it gets worse – some of his distances are apparently accurate down to a one-hundredth of a mile – that’s about 16 metres. And his forecast winds are apparently faithful to one degree and one knot. The fuel remaining in his tanks is precise to one hundredth of a gallon – that’s about an egg-cup full.

Please don’t have stupid figures like that in the cockpit. Simply use the POH fuel consumption figures and plan to land with one hour in the tanks.

Should you bother with deviation? Yes, of course, but you won’t have the deviation card at hand when planning the flight. So, during your round-the-cockpit check, just pull the card out of its holder, below the compass, and check the back to confirm it’s up to date. Then mentally adjust for the error on each leg.

I was taught to draw fine pencil lines on my map so you can rub them out later, but this is a bit silly for two reasons. First, why rub them out if you might fly that route again? And second fine lines can be hard to see – particularly in poor light, or if you need to swop glasses for near and far vision. Rather draw in good solid lines with a marker. Make notes in the margins of your maps. Mark potential landing spots you may need one day. Treat your map rough – it will force you to buy a new one from time to time – which will keep you up to date.

I got lost going to Vic Falls once because I used an out-of-date map.

Work on Minutes per Marker

Now draw in 20 mile markers, and double lines at every 100 miles.

These 20 mile markers are the key to your progress.

If you expect to cruise at say 120 kts the markers give you ten minute intervals. If you find you are passing them every 9 minutes that means you have a tailwind and a groundspeed of 133 kts.

Strangely your actual groundspeed should be of little interest. What really matters is that your markers are now 9 minute markers. And will continue to be so until the wind changes, or until you pick up speed in the descent.

So if ATC suddenly wants your ETA for some obscure spot you can glance at your map and say, okay that’s two and a bit markers away, so it will be slightly more than 18 minutes away – call it 20 minutes.

You may ask why I’m so casual about accuracy. The answer is simple – you are already using the most accurate wind figures available – you have just established them yourself. And it makes no sense to measure the distance within a mile or two because it will amount to less than a minute – so relax and don’t over complicate things.

If anything changes significantly you can always call back with a revised ETA.

Of course you must expect to be late at your first marker because of the climb, so add a few minutes at the beginning, and subtract a couple during the descent.

Finally, your total time to destination is nothing more than a thumb-suck based on met forecast winds. As the trip progresses you get a more and more accurate ETA based on your actual times between markers.

I often flew Cherokees from PE to Wonderboom which is comfortably within a safe range, with an hour’s reserve, as long as there were no strongish headwinds. So my plan was always to see how I was doing at Bloomies. If my ten minute markers had turned into 12 minute markers then I’d stop for fuel. It’s too easy.

We haven’t given much thought to fuel figures. Conventional fuel logs are often a waste of time.

You have to know exactly how much you have in each tank, before the flight. Either use a dipstick, or fill her right up, or use Piper’s splendid little step.

Now can you really be sure how much fuel you used in taxi and climb? Nope. So just use POH figures – not the fuel gauges, and write the time you change tanks, next to your track, or in the margin of the map.

Tips. Actually not tips – RULES.

- Keep the map on your lap with the track pointing forward. This way everything on the map is where it is on the ground.

- The first 20 miles is critical. You must start in the right direction – confirm it with landmarks – both big and small.

- Move your finger up the map as you go.

- Use a 2B pencil to write down the times you pass significant points.

- Look far ahead at the big picture – dams, mine-dumps mountain tops, or whatever.

- If you find you are having to head say 7° to the right of track, then so be it, that’s what the wind is doing to you. Keep allowing that 7° until something changes

- If you stop navigating and paying attention for a while you are likely to get lost.

- Watch out for zeros. Don’t let 002, 020 and 200 confuse you.

- Never alter heading because of a ‘feeling’. That’s a sure way of getting lost. I was testing a pupe on a flight from PE to Grahamstown. He kept feeling he needed to turn ‘a bit to the left’. Eventually we crossed a ridge to find PE straight ahead. He has kept heading ‘a bit left’ until we had done a complete 180. Only alter heading if you have a solid reason.

- Never jump to unfounded conclusions. The words, “That must be Sunnyshoff” are generally a prelude to being lost. Be certain that is Sunnyshoff before you open your mouth.

- Plan to have most of your fuel in one tank for landing.

Maps symbols

Here are some of the more important symbols, and what to expect on the ground.

Note that the map is made in two separate processes. The first is an ordinary topographical map showing mountains, rivers, roads, towns and so on.

Then aeronautical information about airfields, controlled airspace and so on, is printed on top in a dark purple/blue colour.

Look in the margins for the dates that the base and the aeronautical info were printed. Say the base is 20 years old, then it obviously won’t show new roads and dams and the expansion of towns. Railway lines seldom change.

Obviously buy maps with the most recent aeronautical info. The following are important:

All airfields. Orville is 5478 ft AMSL. It has lights and a hard runway (tar). The lighting might only be by arrangement. So phone ahead to check.

If there are radio facilities – ATC, or nav-aids – they will be listed at the top of the box. And if there is customs then the airfield name will have a dashed box around it.

Make sure you don’t confuse military and civil airfields – this can land you in a lot of distress.

The little maroon triangle is a compulsory reporting point. Normally an FIR boundary or TMA.

Cities, towns or villages may have developed or merged since the base was printed.

The tiny little circle – a ‘Place of local importance’ – may actually be very important to you. Perhaps it is a truck-stop, trading store or post office in a desolate area. Look for tracks and paths radiating from it.

The railways are useful – they don’t change over time. The minute symbol for a station or siding may also be the focal point of radiating tracks.

Power lines are obviously significant to low flying aircraft, but they are also good navigation features, and easy to see because of their direct routes, and a clear ground below them for service vehicles.

A mine, depicted by a tiny crossed pick and shovel, can be anything from a hole in the ground to a massive mine dump you can see 50 miles away.

Spot elevations are mostly worthless. They may only be a hump that is slightly higher than the surrounding ground. Or they may just be surveyed points that have white stones round them.

With radio masts the top figure is the height that you would just hit them if you are using QNH. The number in brackets is the tallness of the mast. They can be useful as they are often on the highest point of a hill or ridge. Low-flying enthusiasts beware – masts have a wide net of support cables.

Nav-Log

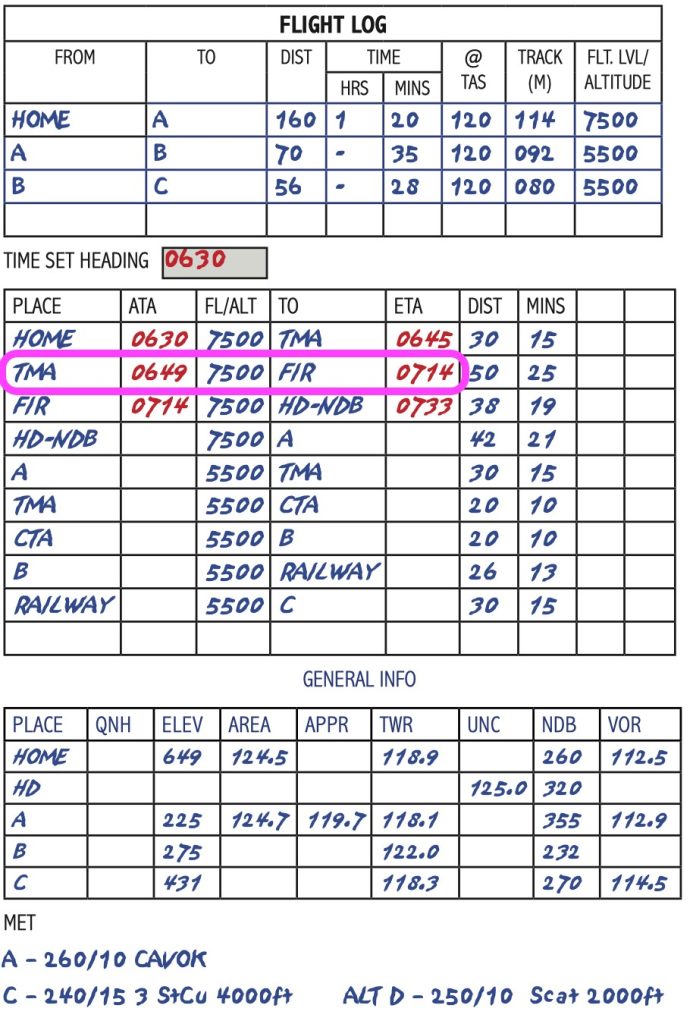

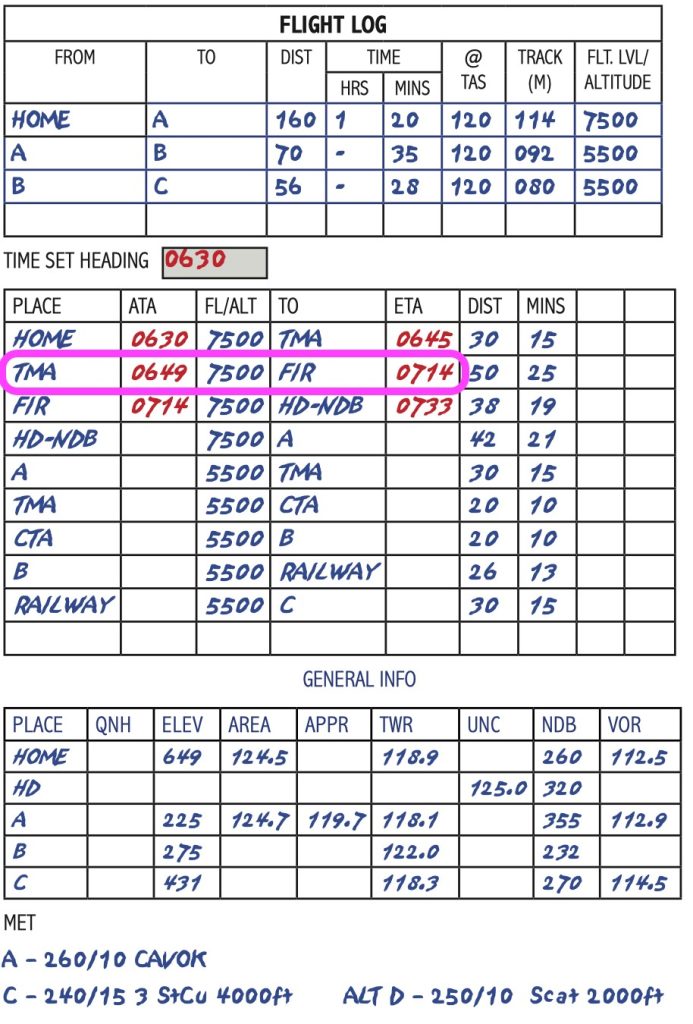

Although map-only nav works 100 times better than too much paper, I suggest you teach pupils to use this nav-log.

It has everything you need, and nothing you don’t need. The best part is that you don’t have to think about position reports – you simply read them off. Look at the bit I have circled – your position report goes, TMA 0649, 7500ft, FIR 0714.

Magic stuff.

Map reading is a fun way to navigate – get your spouse and kids involved in spotting places and working out ETAs – they will love it.

Insert “Flight Log A to C.jpg”